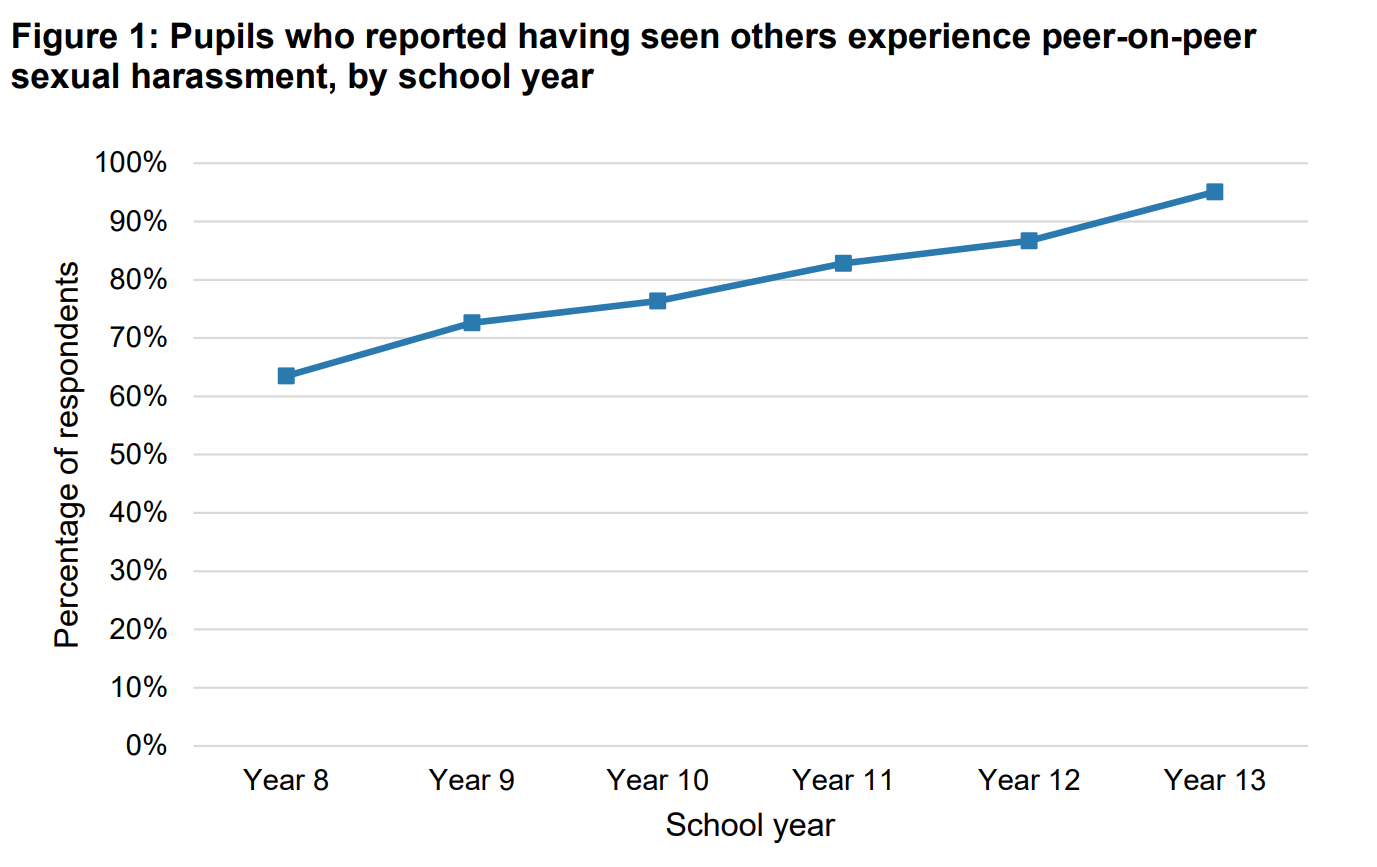

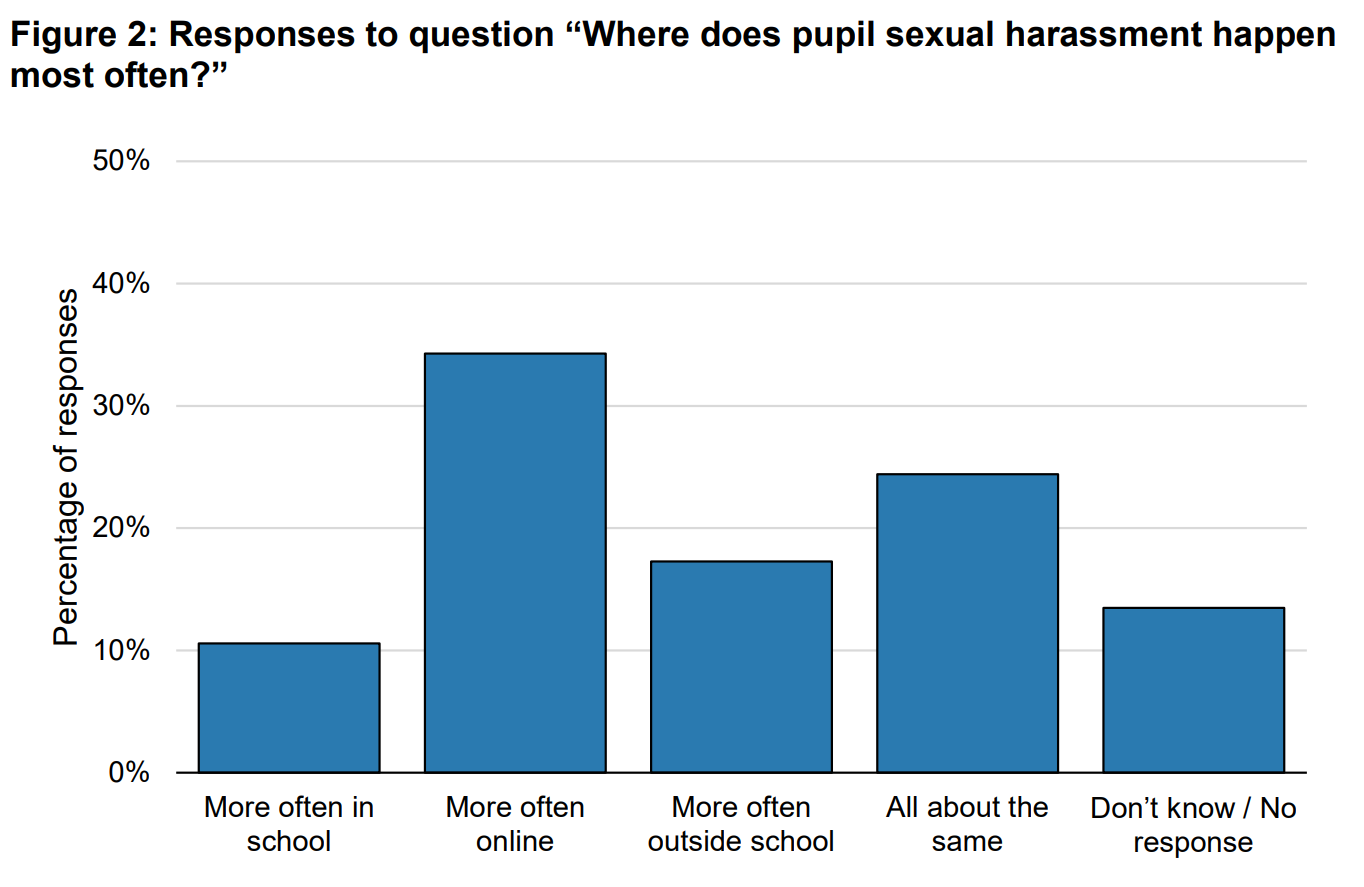

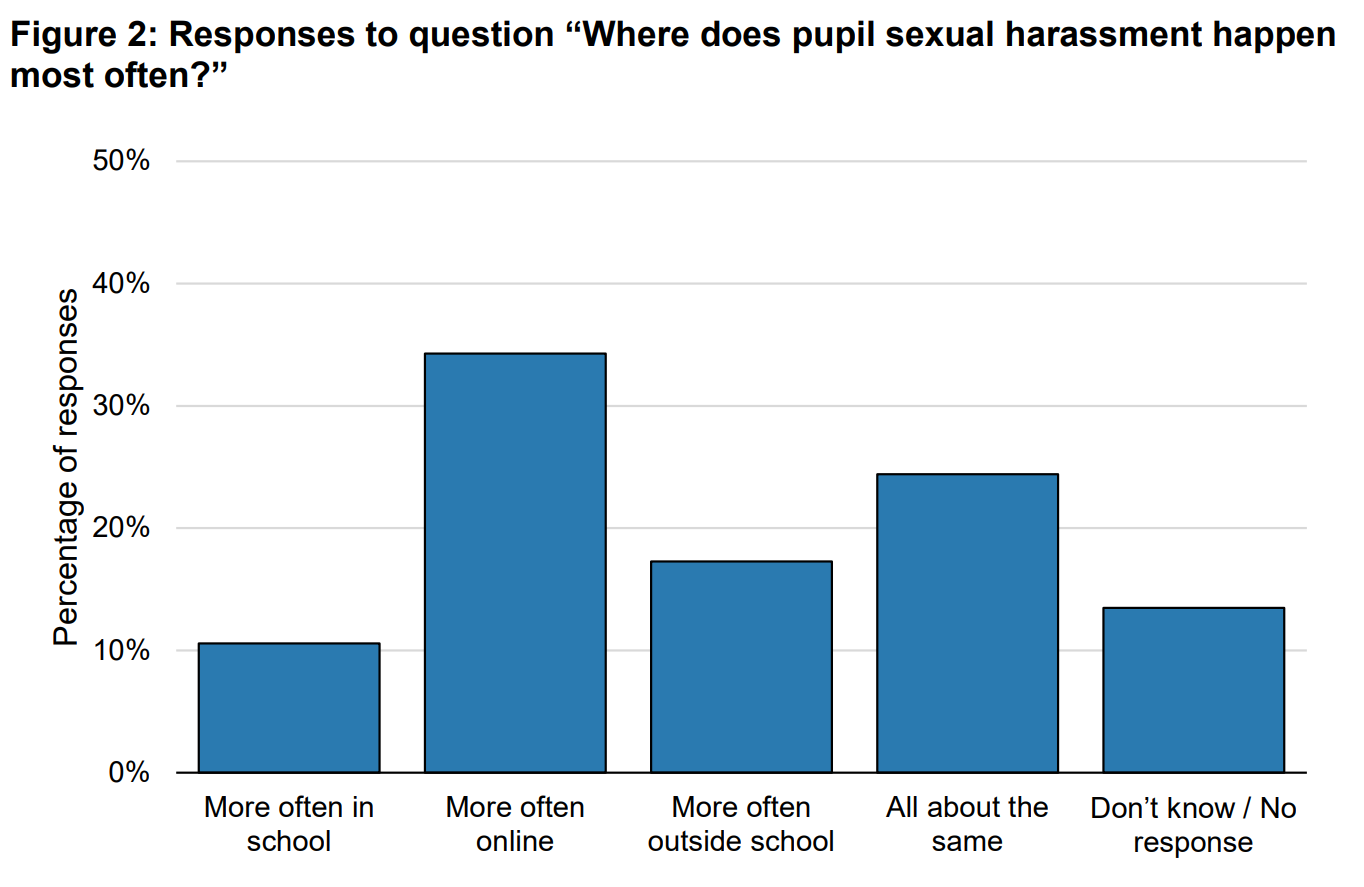

Pupils say that peer-on-peer harassment happens more online than in school (Figure 2). They speak comprehensively about mobile phones, social media and gaming sites and the issues associated with them.

These are the main themes associated with online activity as identified by the pupils:

- peer pressure to have a high number of online ‘friends’, ‘likes’ and comments on profiles

- online bullying, posting hurtful comments about peers, in particular comments about appearance

- sexual objectification of photos of girls by boys

- asking for, sending and sharing nude or semi-nude photographs

- catfishing, unsolicited friend requests or demands for nude photos by strangers or those with a fake social media profile

- negative attitudes towards female characters and/or when girls play digital games

Despite the fact that young people value owning a mobile phone, they understand how the problems associated with them can impact negatively on mental health. From their comments it is clear that young people feel there is a pressure to post popular comments regularly and to be ‘liked’ on social media.

“You are made to feel like you have to post to please people and get likes. There is pressure to post 24/7.”

Boys and girls alike talk widely about online peer pressure to be popular on social media and needing to gain ‘likes’ and ‘followers’.

Hurtful comments by peers are more commonly made online than in school. Girls, in particular, receive negative comments from other girls because they have shared a photo of themselves on their profile page on social media. They feel pressure to conform with certain expectations about shape and looks as they perceive that attractive young girls regularly post pictures of themselves, expecting others to make complimentary comments about them and the way they look. Boys admit to sending and receiving vulgar comments and texts from other boys, often related to body shaming or making fun of other boys’ posts. They perceive this to be “normal”.

In a few instances, there is more targeted bullying between girls where they spread rumours about other girls’ sexual activity, dare other girls to have sex or send photos of themselves in their underwear. Girls then share these photos around and call them names such as “slag” and “slut”.

“There is a lot of bullying on social media. People pick on other people because of looks. This could mentally impact people, especially if someone calls you a ‘whore’ or a ‘slag”.

A minority of girls are concerned about the effects of online bullying, saying that this can lead to anxiety, depression and body dysmorphia, which could also lead to eating disorders and self-hatred.

In terms of sexting, sexualisation of peers and sending nude photographs, nearly all pupils from Year 10 onwards identify common issues. However, many do not realise that this is a criminal act and the impact of a criminal record on their future career or aspirations following prosecution. By sending or receiving a naked picture, a child may commit criminal offences relating to the creation and distribution of indecent images of children under section 1 of the Protection of Children Act 1978 (which includes images of those aged 16 and 17 by virtue of section 45 of the Sexual Offences Act 2003), section 160 of the Criminal Justice Act 1988 and section 62 of the Coroners and Justice Act 2009. Sexting by children could also lead to causing or inciting a child to engage in sexual activity under section 8 (child under 13) or section 10 (child) of the Sexual Offences Act 2003.

It is evident that pressure to share nude photographs, the loss of control over images once they have been shared and young people being made to feel guilty when they don’t send photos is commonplace among older pupils. Most girls say that boys asking for nude photographs of them is a regular occurrence and speak about the constant pressure from boys to send photographs. For example, one girl noted, “It is a daily occurrence – it is very common. Boys ask for nudes or keep spamming your phone.”

Most girls are aware of the dangers of sending photos via text and the threat of anyone sharing them further. All girls who talk of their experience of sexting say that it is only boys who ask for nude photos but a few of them also blame girls for complying “just to please boys and to be more liked or loved”.

More than half of the boys speak about being personally involved in sexual harassment of peers, for example harassing girls with nude images of strangers or other inappropriate photos or videos. Boys also talk about the pressure by other boys to send nudes or sexual content. Many boys say sharing nude photographs of girls amongst their friends and boasting about the number of nude photographs they have in their possession is commonplace. Although they admit to doing it, the majority of boys acknowledge that this is wrong and disrespectful.

A minority of older boys say that pornography is shared around as “boys want to impress their friends”. Normally the content is not of someone they know. When asked if they think this is acceptable – a minority comment that it is “ok as long as you don’t know the girls in the pictures”. Overall, only a few LGBTQ+ pupils say they have personal experience of sexting, stating that members of the LGBTQ+ community have more respect for each other than other young people. One shared…

“We are more private, and we look after each other because no-one else does. We talk about it in the LGBTQ+ club. Nothing really happens after, but we get to talk about it.”

Many boys identify grooming by older people as a significant online risk. This includes unknown people contacting boys and sending ‘friend requests’, which they say is a regular occurrence. A minority of boys note that random people often come online and that it is “too easy to communicate with people you don’t know” via online games. Nearly all are aware that they shouldn’t talk to people they don’t know online or accept friend requests from strangers.

Pupils speak knowledgeably about catfishing where pupils create fake accounts to send unsolicited images and harass other pupils. They state that catfishing is a common problem and usually involves older men targeting young girls. A substantial number of girls say they have been targeted, usually by receiving inappropriate pictures and texts from strangers and not from peers through a popular digital social media app.

The majority of young people know how to identify fake accounts and feel able to block them. Most young people understand the term ‘grooming’ and say they would report it if it happened to them. Older girls talk of receiving messages from unknown men and boys on a social media site that is popular for sharing photographs, asking them to send images of themselves, “begging us for nudes”.

Most boys say that they have played games that they are legally too young to play. Older boys say they play these games regularly and enjoy them whilst the younger boys say they are pressurised into swearing and “talking dirty” when playing these games. Boys in the sixth form have a reasonable awareness of the level of toxicity of language used in gaming fora, including the normalised use of terms such as “slut” and “whore” when referring to women. Girls who speak about this mostly identify a problem around inappropriate games that often shame women. Girls speak about the sexist portrayal of women in games that are popular with boys, where girls are treated in a derogatory and sexualised manner. A few boys adopt this tone in the way they speak to girls during online games,

“Boys treat women differently because games portray women as being inferior to men.”