Boys and girls offered comprehensive responses to the mobile phone image and the possible scenarios associated with it. Generally, all girls’ responses were very similar to each other as were boys’ views of the problems associated with the phone. Nearly all of the commentary was about problems and negative experiences and only a handful of pupils chose to write about the benefits of having a mobile phone and the pleasure it gave them.

Boys and girls offered comprehensive responses to the mobile phone image and the possible scenarios associated with it. Generally, all girls’ responses were very similar to each other as were boys’ views of the problems associated with the phone. Nearly all of the commentary was about problems and negative experiences and only a handful of pupils chose to write about the benefits of having a mobile phone and the pleasure it gave them.

There were five main themes associated with the mobile phone as identified by the pupils. These were:

- peer pressure to have a high number of online ‘friends’, ‘likes’ and comments on profiles

- online bullying, posting hurtful comments about peers, in particular comments about appearance

- sexual objectification of photos of girls by boys

- asking for, sending and sharing nude or semi-nude photographs

- catfishing, unsolicited friend requests or demands for nude photos by strangers or those with a fake social media profile

- Negative attitudes towards female characters and/or when girls play digital games

Despite the fact that young people highly value their mobile phones they explained clearly the problems associated with them and how these can impact negatively on mental health. From their comments, it was clear that young people feel there is pressure to post popular comments regularly and to be ‘liked’ on social media. There was clear evidence of teenagers spending a lot of their time on social media posting and generating support.

“You are made to feel like you have to post to please people and get likes. There is pressure to post 24/7.”

They felt that this, together with their experiences of online bullying and harassment, impacted on their mental health and harmed their self-esteem and confidence. Most of the girls described the main problem with mobile phones as one of young people comparing physical looks with others.

Many young people mentioned receiving inappropriate messages and general bullying around this. For example, many described how girls can receive negative comments from other girls because they have shared a nice photo of themselves. A minority of girls mentioned the pressure to conform with certain expectations about shape and looks where attractive young girls regularly post pictures of themselves expecting others to make complimentary comments about them and the way they looked. In a few instances, there is more targeted bullying between girls where they spread rumours about girls’ sexual activity, dare them to have sex or to send photos of themselves in their underwear, then share these photos around and call them names such as “slag” and “slut”.

“There is a lot of bullying on social media. People pick on other people because of looks. This could mentally impact people, especially if someone calls you a whore or a slag.”

A minority of girls were concerned about the effects of online bullying, saying that this could lead to anxiety, depression and body dysmorphia which could also lead to eating disorders and self-hatred. A very few talked about female friends who had experience of some of these issues.

Boys also talked widely about online bullying and peer pressure. They mentioned the pressure to be popular on social media and needing to gain ‘likes’ and ‘followers’. Whilst admitting to doing this themselves, many realised that being in contact with strangers could lead to issues. Many boys’ responses were around sending and receiving vulgar comments and texts from other boys, often related to body shaming or making fun of other boys’ posts. Younger boys in Year 8 and a few in Year 9 associated this image with general bullying and saying nasty things to each other, not necessarily about their sexuality, gender or the way they looked. They were aware of how a phone or social media can be used to sexually harass others, but many had not come across any examples themselves.

In terms of sexting, sexualisation of peers and sending nude photographs, nearly all pupils from Year 10 onwards identified common issues. It is evident that pressure to share nude photographs, the loss of control over images once they have been shared and young people being made to feel guilty when they don’t send photos is commonplace. Most girls identified boys asking for nude photographs of them as a regular occurrence and spoke about the constant pressure from boys to send photographs. “it is a daily occurrence – it is very common”. A few of the older girls stated that they felt they had no choice but to comply.

“Boys ask for nudes or keep spamming your phone.”

Most girls knew of the dangers of agreeing to send photos via text, especially when they or their friends were wearing bikinis. They were very aware that the threat of anyone sharing them further afield was very real. A few girls said that they have received messages asking for photos of themselves naked – generally from boyfriends, who they all said ended the relationship straight after. All girls said that it is only boys who ask for nude photos but a few of them blamed girls for complying “just to please boys and to be more liked or loved”. In a few focus groups, girls said that boys often posted on social media that they have had sex with them when this isn’t true – often making stories up and boasting about sexual exploits.

More than half of the boys spoke about being personally involved in sexual harassment of peers, for example harassing girls with nude images of strangers or other inappropriate photos or videos. Boys also talked about the pressure by other boys to send nudes or sexual content unwillingly. Many boys spoke about the prevalence of boys sharing nude photographs of girls amongst their friends and boasting about the number of nude photographs they had in their possession. In the majority of cases, boys acknowledged that this was wrong and disrespectful. A few boys felt that sending or receiving rude messages was equally as bad, because those boys who received them would nearly always share them with their friends, even though they knew they should report them or delete the message. In some focus groups, many boys said that they have sent their male and female friends sexual comments in texts, saying this is common and only a bit of fun, “everyone expects it”.

“We will often send comments to each other slagging girls or boys off because of what they look like or they will say that they have had sex with them when this is not true.”

A minority of older boys said that porn is shared around as “boys want to impress their friends”. A few boys said that they had been sent pornographic or rude photos but not of girls they know. When asked if they thought this was acceptable – a minority commented that it was “ok as long as you don’t know the girls in the pictures”.

Overall, only a few LGBTQ+ pupils said they had personal experience of sexting, but many had heard of pupils being asked to send nude photos of themselves to girl/boyfriends. A few said that members of the LGBQT+ community have more respect for each other than other young people.

“We are more private, and we look after each other because no-one else does. We talk about it in the LGBTQ+ club. Nothing really happens after, but we get to talk about it.”

When inspectors discussed sources of support for online sexual harassment, sexting and issues around sending nude photographs, pupils typically said they would reach out to their friends. A few noted that they have had some teacher-led activities to highlight the dangers of sexting and have been encouraged to report any incidents to their head of year. Whilst many pupils understood the need to report any activity of peer-on-peer sexual harassment on social media, they did not typically state that they would tell their teachers.

Most pupils refer to problems with ‘catfishing’ where pupils create fake accounts to send unsolicited images and harass other pupils. Pupils stated that catfishing was a common problem and was usually older men targeting young girls – a substantial number of girls said that they had been targeted. A minority of girls noted that they had received inappropriate pictures and texts from strangers and not from peers. They referred to these as unwanted and upsetting.

It is clear that the majority of young people knew how to identify fake accounts and felt able to block them. Most young people understood the term ‘grooming’ and said they would report it if it happened to them. Many wrote about the dangers of meeting people they don’t know, especially if they have been asked to send photos of themselves. They said that they would not ‘friend’ anyone on social media that they didn’t know. Older girls talked of receiving messages from unknown men and boys on Instagram asking them to send images of themselves, “begging us for nudes”. When asked about what they would do in these situations and whom they would turn to for support, many pupils said they would ‘block’ the perpetrator, report the matter to a friend, teacher or parent or ask the police for help.

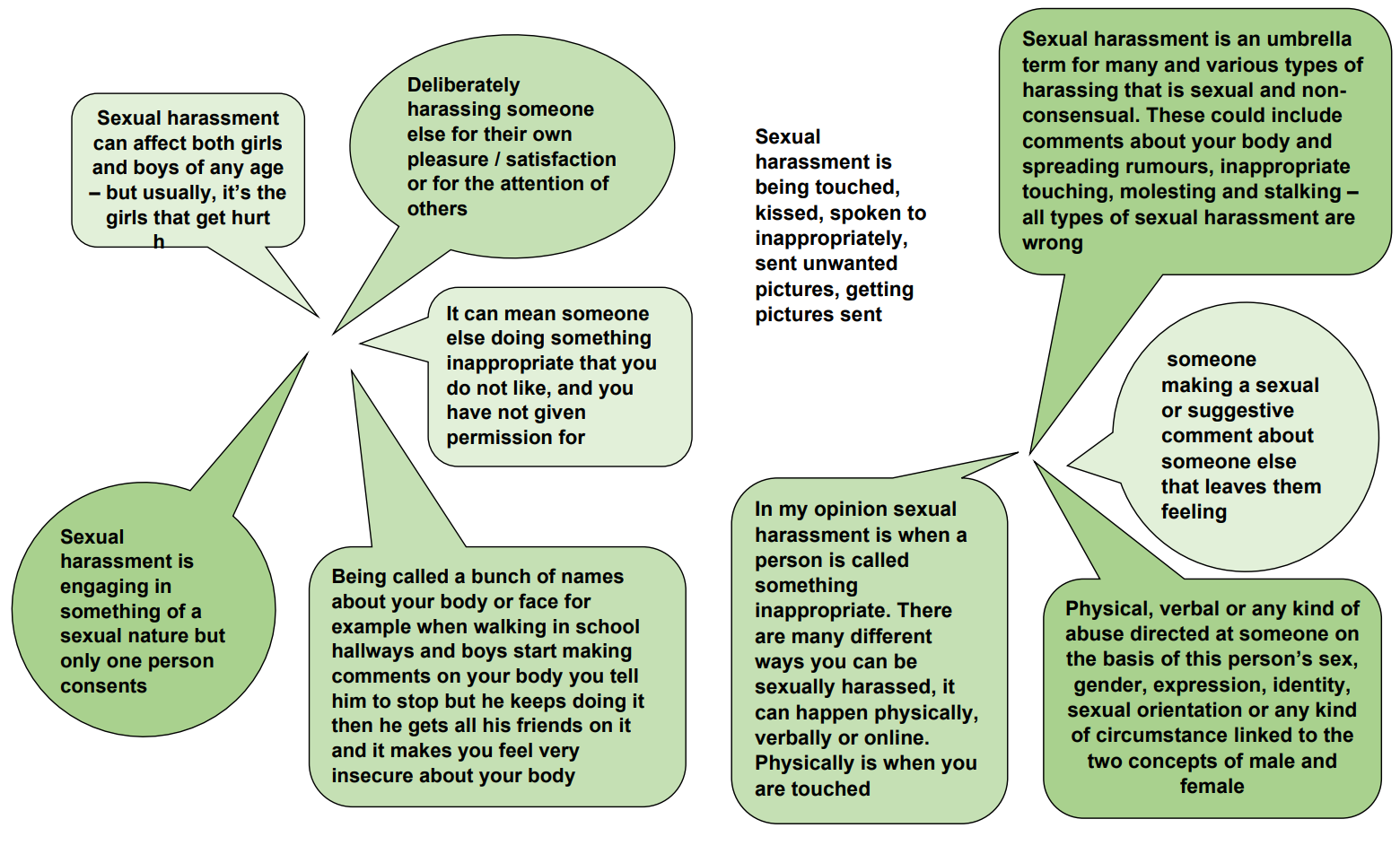

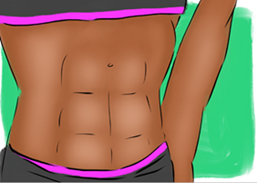

The types of harassment mentioned mostly involved ‘fat shaming’, unwanted touching, the sexualisation or objectification of the body – both for boys and girls – and issues around fitness. The ‘six pack’ image also triggered a number of comments around cat‑calling, name calling and public body shaming.

The types of harassment mentioned mostly involved ‘fat shaming’, unwanted touching, the sexualisation or objectification of the body – both for boys and girls – and issues around fitness. The ‘six pack’ image also triggered a number of comments around cat‑calling, name calling and public body shaming.  Boys and girls offered comprehensive responses to the mobile phone image and the possible scenarios associated with it. Generally, all girls’ responses were very similar to each other as were boys’ views of the problems associated with the phone. Nearly all of the commentary was about problems and negative experiences and only a handful of pupils chose to write about the benefits of having a mobile phone and the pleasure it gave them.

Boys and girls offered comprehensive responses to the mobile phone image and the possible scenarios associated with it. Generally, all girls’ responses were very similar to each other as were boys’ views of the problems associated with the phone. Nearly all of the commentary was about problems and negative experiences and only a handful of pupils chose to write about the benefits of having a mobile phone and the pleasure it gave them.

More boys than girls selected the games controller and had more to say about the problems associated with online games. In a few schools, none of the girls chose this image in any of the focus groups. Girls who spoke about this mostly identified the problem around inappropriate games that often shame women. Girls spoke about the sexist portrayal of women in some games where girls are treated in a derogatory and sexualised manner. Girls said that a few boys simulate this tone in the way they speak to girls during online games. One girl said,

More boys than girls selected the games controller and had more to say about the problems associated with online games. In a few schools, none of the girls chose this image in any of the focus groups. Girls who spoke about this mostly identified the problem around inappropriate games that often shame women. Girls spoke about the sexist portrayal of women in some games where girls are treated in a derogatory and sexualised manner. Girls said that a few boys simulate this tone in the way they speak to girls during online games. One girl said,  The image of the lips generated comments about physical appearance, make-up and the issue of consent. In a very few cases, pupils identified general bullying and hurtful comments as main issues from the lips image. Only a minority of pupils selected the lips image to discuss and more girls than boys wrote comments.

The image of the lips generated comments about physical appearance, make-up and the issue of consent. In a very few cases, pupils identified general bullying and hurtful comments as main issues from the lips image. Only a minority of pupils selected the lips image to discuss and more girls than boys wrote comments.  Generally, across all focus groups, only a few chose the scenario of the school corridor as a place for problems. In a majority of schools, no pupil discussed or wrote about serious issues relating to the school corridor. The most common themes were generalised bullying and name-calling, sexualised comments being made and homophobic bullying. A few of the older girls spoke about catcalling in the corridors.

Generally, across all focus groups, only a few chose the scenario of the school corridor as a place for problems. In a majority of schools, no pupil discussed or wrote about serious issues relating to the school corridor. The most common themes were generalised bullying and name-calling, sexualised comments being made and homophobic bullying. A few of the older girls spoke about catcalling in the corridors.  Only a very few pupils selected the image of the school toilets to discuss potential issues. There were a few common comments from the pupils. These were related to feeling uncomfortable or unsafe because of the possibility of someone looking over the top or under the bottom of toilet doors, fears of being filmed by peers and possible voyeurism from unknown adults. There were a few comments by concerned pupils about the quality of toilets and the prevalence of doors that didn’t lock properly.

Only a very few pupils selected the image of the school toilets to discuss potential issues. There were a few common comments from the pupils. These were related to feeling uncomfortable or unsafe because of the possibility of someone looking over the top or under the bottom of toilet doors, fears of being filmed by peers and possible voyeurism from unknown adults. There were a few comments by concerned pupils about the quality of toilets and the prevalence of doors that didn’t lock properly.  Less than 5% of pupils chose to discuss the school bus. There was no common theme other than verbal bullying including homophobic name-calling, more often from older pupils. A few commented on how it was easier to physically abuse peers on the school bus because of the lack of supervision.

Less than 5% of pupils chose to discuss the school bus. There was no common theme other than verbal bullying including homophobic name-calling, more often from older pupils. A few commented on how it was easier to physically abuse peers on the school bus because of the lack of supervision.